This is the seventh post in the series, Modeling Deployment Pipelines. In our last post we saw how deployment pipelines are powered by Agents and Environments. In this post, we’ll cover ways to make your pipeline more flexible and some techniques to help during an emergency.

What is a Hotfix

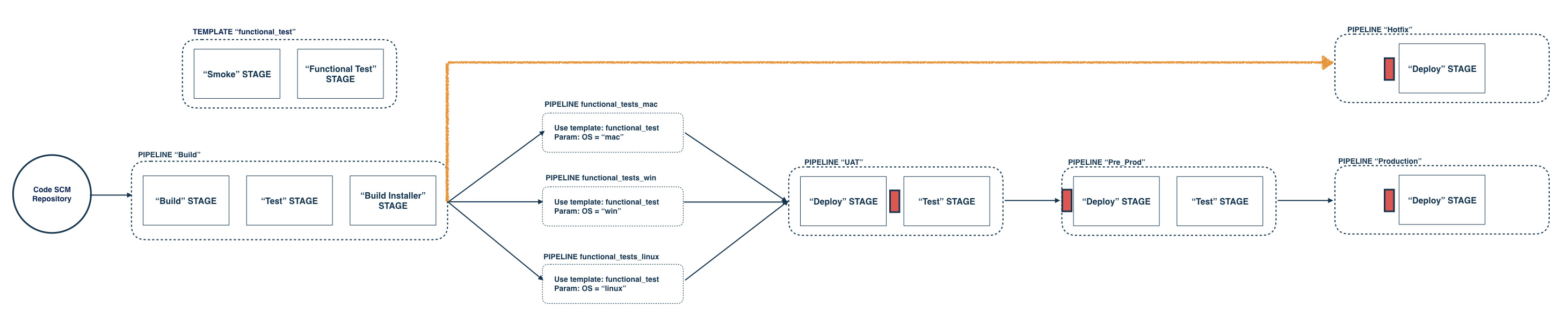

While it’s best not to rely on them, when used in rare cases hotfixes can be a life-saver. A hotfix is essentially a pass to go directly into production. It can be modeled as shown below:

Click image to zoom in

Click image to zoom in

The red gate in the image above signifies a manual gate.

What is the best way to model a “Hotfix”?

The above image is just one of the ways you could model hotfixes. As these are not truly certified builds you’re putting into production, it would be wise to keep these pipelines paused and have strict controls over who can trigger them. Hotfixes can be modeled this way because of the recommendation to move the actual deployment logic into scripts which are checked-in locally. In this case, the “Hotfix” pipeline is almost exactly the same as the “Production” pipeline. The only real change is that it fetches its deployment artifact directly from the “Build installer” stage.

Rollback or Roll-forward

A similar approach can be taken for rollbacks. There’s always a question of whether rollbacks are appropriate or whether it should always be a roll-forward. That is not a decision made lightly. It depends on the culture and ability of the team and the maturity of the codebase being worked on.

A quick roll-forward is preferable to a rollback.

If the codebase and the CD pipeline are setup properly with an appropriate set of tests, then the number of times a really bad build goes into production (requiring a rollback) should be extremely small. If you find that you need to roll back too often, it is a sign that you need to stop and take a look at the processes and checks and balances in your CD pipeline and find out what’s missing.

Having said that, here are some approaches to creating a rollback or roll-forward:

1. Re-running an old pipeline run

Depending on the kind of application being deployed, a “rollback” might just be the deployment of an older build. In cases such as a static website or an application without state, this is appropriate.

2. Having a “roll-forward” pipeline exactly like the “hotfix” pipeline shown above

If you’re really sure that this will only be used judiciously, a “hotfix” pipeline can double as a “roll-forward” pipeline in a pinch. It’s a risky approach, though. A better approach, if your end-to-end pipeline runs quickly enough, is to make a commit and let it run through the whole pipeline and then deploy a fully tested build. You should probably then go back and do a root cause analysis of how a bad build went into production.

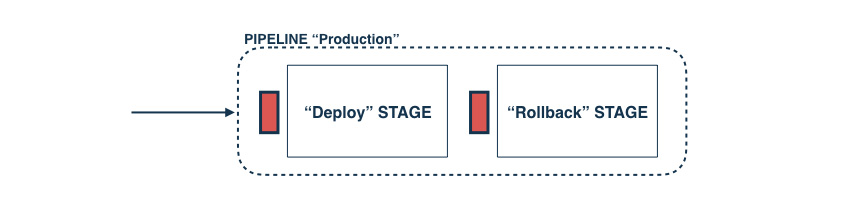

3. Use a “rollback” stage with a manual gate

You can have a “rollback” stage at the end of your “production” pipeline, as shown here:

The advantage here is that you can see exactly which version has been deployed (in GoCD’s pipeline history page) and you can run the “Rollback” stage for that version. You could set it up so that that “Rollback” stage just undoes any state change created by the “Deploy” stage of the pipeline. Since the “Rollback” stage is part of the same pipeline, all the environment variables and upstream dependencies used by the “Deploy” stage can be used by the “Rollback” stage too.

In summary, a rollback or roll-forward can be orchestrated by the CD tool as a part of the workflow, but the actual process of the rollback or roll-forward is highly specific to the application you’re building. This is why rollback strategies (and even the way to set-up your deployment pipelines) need to be thought out depending on what makes sense for the application and the business, rather than expecting a CD tool to magically provide a solution.

There are many more concepts to explore in modeling deployment pipelines like implementing feature toggles, performance tests, microservices, security tests etc. Let us know what you’d like to hear about in our next post in the comments section below.